Studs

Nailed studs, screw-in studs and the "Miracle of Berne"

Anybody wearing heavy nailed football boots today? Probably not. Today's football shoes weigh about 200 grams, look as if they had been moulded to the player's foot and all materials used are either glued or welded. Early football boots, by contrast, rather looked like today's safety shoes or mountain boots.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the owner of a pair of leather shoes was virtually considered wealthy, since many people, in rural areas, in particular, used to wear wooden clogs or straw footwear, or no footwear at all, except on Sundays. If you had leather shoes you would wear them for working and in your scarce leisure time, and you would have them repaired again and again if damaged. This is nearly unimaginable in the era of low-priced footwear and fast changing fashion trends, yet it is an explanation why the boot shown in Figures 1 and 2 looks like a much-worn work boot of a miner - for this is what it was originally.

For use in football, the shoe shown in Figure 2 has nearly square leather cleats as main anti-slip footgrip, hammered onto the outer face of the sole.

Another example (Figure 3) shows two leather bars at the ball area of the sole and three round leather studs at the heel. Horse-shoe shaped attachments (see Figure 4 from the year 1949), mechanically attached round studs or bars in various shapes were used very early. Their size and shape have a decisive influence on the overall stability of the player, his "footing". They also determine the likelihood of clogging with bits of turf. You can see in Figure 5 how stubbornly dirt can get stuck between the studs. This effect will be stronger or weaker, depending on the geometric arrangement of the studs, their material and degree of wear. Originally, the studs had been similar to those shown in Figure 6.

Frequently, studs were extended to stud strips, for example as developed by Vorwerk & Sohn from Wuppertal-Barmen, known today for their vacuum cleaners, who had a specific shape patented in 1938 (DE 689 237 A, Figures 7 and 8).

All nailed studs have a huge disadvantage: they can break off, damage the sole and, if it comes to the worst, ruin the whole shoe. Replacement studs therefore often had to be fitted in slightly different places to obtain satisfactory fastening. For this reason you can often find a series of nail wounds in the soles of historical, much-used shoes, the last set of studs being located in places where you can virtually see the wearer's pain (compare Figure 2). This is why nailed studs were exchanged as seldom as possible although they were not always well adapted to the weather and the resulting pitch conditions. For this reason, ideas were developed at an early stage how to change studs as needed.

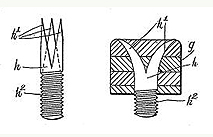

The 3:2 victory of Germany's national team in the 1954 FIFA World Cup final over the apparently unbeatable Hungarian team - at any rate they had not been defeated for the previous four years - has become a legend in Germany. It founded the fame of the then kit manager of the German national team, Adolf Dassler. The pitch had become more and more deep and slippery due to heavy rain (referred to as "Fritz Walter weather") in the first half. Dassler attached the appropriate screw-in studs (compare Figures 9 and 10) to the complete team's shoes in a record time during the halftime break, whereas the Hungarian team had to play with short and soft cork nubs nailed to the soles. It is not astonishing that the 1954 FIFA World Cup is collectively remembered as the birth hour of the screw-in stud shoe.

Maybe it is because of this legend status that reports will be published before any major football event claiming that Adolf Dassler was not the true inventor of the screw-in stud. This, however, is common knowledge for any expert.

The development of football shoes with screw-in studs had actually started at least 30 years before 1954 (in other sports, such as baseball, there are even earlier examples). A large variety of stud types was already known at that time. As briefly outlined in the "Football Footwear" chapter, section 3.2., Ludwig Wackler (DE 443 311 A, 1925) and Venustus Eigler (DE 530 454 B, 1930), for example, had obtained patents for solutions in this field. According to their inventions, leather strips or individual plates provided with thread sockets for receiving threaded studs were attached subsequently to the sole of a football shoe.

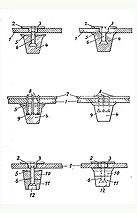

In his patent specification of 1925, Ludwig Wackler refers to screw sleeves, inserted between insole and outsole in the manufacturing process, as prior art. This implies that a football shoe had existed at that time which had been designed for removable studs. However, there is no precise evidence of such a shoe in patent literature. Not only German inventors were active in this field. As early as in October 1924, the French inventor Louis Deschamps obtained a patent for an aluminium plate with milled sockets (FR 29 546 E) that covered the ball or heel area of a football shoe. Even earlier, in July 1922, George Bell had proposed to insert individual thread sockets between the inner sole of the shoe and another, lower layer above the outsole (US 1 515 330 A). An even older patent proposed to hammer pins, threaded at one end and provided with three prongs at the other end, into the sole of a football shoe (GB 186 643 A, 1921). The prongs spread out when they are driven into the sole layers so as to provide sufficient grip to allow to attach studs with internal threads to the threaded part (see Figure 11).

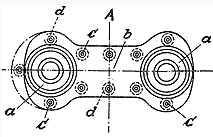

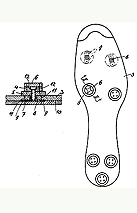

The majority of the mentioned examples still relate to rather robust footwear. Alexander Salot presented a much-cited development of a lightweight flat shoe in 1949. He invented a screw sleeve attached under the outsole using a two-ended component, shaped like a propeller (Figure 12). Mr. Salot fitted a premier league team out with his stud shoes, and renowned German clubs like Hamburger SV, Rot-Weiß-Essen or FC Schalke 04 ordered samples (as recorded by the magazine Der Spiegel in issue 9/1950, p. 28).

And if Rahn had not scored at the 1954 final? It is pointless to discuss whether Adolf Dassler would have become that famous. Maybe not, for he quite certainly had some luck to be in the right place at the right time.

However, it should not be overlooked that he had developed a shoe with outstanding stability. The main technical background of his invention is the idea that the base plate of the screw sleeve should be as large as possible. This plate is located above the outsole, which has to be pierced for the screw sleeve. He implemented this - to put it in simple terms - by means of a washer, flattened at the boards, provided in the centre with a heightened thread sleeve which exactly filled the hole in the sole. Due to its position between the outsole and the insole layers, the shape of the washer provides for specific stability against breaking off and firmly anchors the thread sleeve and the stud in the shoe (compare Figure 9, DE 16 95 594 U). This is a decisive advantage over the concepts of his precursors whose shoes had been much more damage-prone.

A small washer might not be suitable to create a legend, but it has been a decisive component in the success story of shoes featuring screw-in studs.

Finally, here is an overview of a large variety of studs from the years 1954 to 1970, which players could attach to their shoes depending on weather and pitch conditions (Figure 13).