Radio flag

Chronicle of difficult communications:How referees became inventors

It all started with a cablegram sent from Santiago de Chile in May 1962 and ended eight years later and some thousand miles further north, when the first yellow card in the history of football was shown.

Maybe Corrado Pizzinelli, a journalist of the Italian newspaper Naziones, who had been sent to Chile to cover the 7th FIFA World Cup, had been desperate waiting ten days for the opening whistle of the tournament or, so the legend goes, possibly felt resentment towards an impudent hotel manager, when he sent his first report to his faraway home country. He cabled home that he felt "condemned to live in that sad and fantastic world where the events of that unforgettable novel "The Opposing Shore" (Le Rivage des Syrtes) by Julien Gracq took place".

Pizzinelli's detailed and hapless comments on the host country, collected under the title "The infinite melancholy of the Chilean capital - Santiago, the end of the world", in which he did not even refrain from commenting on the honour and grace of Chilean women as compared to Turin women, were not only read in Italy, but also transmitted to a Santiago broadcasting station by an employee of the cablegram company.

The Group B first round match on 2 June 1962 at 3:00 p.m. between Chile and Italy is remembered as the most violent match in the history of the FIFA World Cup.

After the Italian players, in an attempt to mollify the audience, had thrown carnation posies to the spectators which the latter returned post-haste, tensions erupted on the pitch. Another contributing factor was that the Italian team felt under enormous pressure to succeed after their first round match against Germany had been a draw (0-0). Italy's midfielder Ferrini was the first player to be sent off in the 7th minute, but the offender obstinately refused to leave and had to be led away by police while the match was halted for ten minutes.

In the course of the game, which later became known as "the battle of Santiago", the English referee Ken Aston was able to punish just a few of the many offences committed. The most violent incidents, overlooked by Ken Aston, were two retaliatory punches by Chilean outside-left Sánchez flattening the Italians, Maschio and David. At the end of that match - an encounter that only partially had to do with football - even the old saying was proved wrong according to which a match lasts 90 minutes. Aston blew the final whistle after a brawl erupted when Chile had scored 2-0 in the 88th minute. Having injured his Achilles tendon, Aston did not referee another football match after that.

However, the Briton was soon appointed FIFA adviser for refereeing and, four years later, in his new function as Head of the World Cup Referees he witnessed his German referee colleague Rudolf Kreitlein experiencing a similar drama at Wembley Stadium. In a tough encounter between England and Argentina in the 1966 World Cup quarter-finals, Kreitlein had cautioned three players on each side after just 30 minutes and soon he had entered the entire Argentine team in his notebook. Argentine captain Rattín was dismissed in the 35th minute when he wildly gesticulated at Kreitlein after a free-kick decision. Rattín did not leave the pitch - allegedly not understanding the sending-off and demanding an interpreter to communicate his appeal against the referee's decision.

Being very experienced in such situations, Ken Aston hurried to the pitch after eight minutes and persuaded Rattín to give up his protest. Afterwards Aston analysed the incidents and realised that one of the vital reasons for the scandal was that hardly any of the players warned by Kreitlein in the course of the game were aware that they had, in fact, been cautioned. The solution of this communication problem came to him when he drove home from the stadium at a traffic light on Kensington High Street.

So the yellow and red cards were born and used for the first time in the next World Cup in Mexico in 1970.

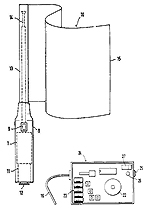

Soon afterwards, Rudolf Kreitlein also rendered outstanding services to communication on the football pitch. Not only from personal experience Kreitlein knew that, if the referee and the linesman made eye-contact too late or not at all, this could lead to controversial game situations or even an error that might be decisive for the game. He invented a device to ensure reliable communication between the referees and the linesmen, the so-called "Funk-Commander" (radio commander) (cf. Figure 1), which certainly would have helped Ken Aston a great deal in his last appearance as an active World Cup referee.

In 1981, he presented the radio commander at the ISPO trade fair in Munich, at the same time applied for a patent and presented the invention in a TV programme "Das aktuelle Sportstudio" to a sports interested audience. The communication system invented by him (DE 31 20 584 A1) consists of a transmitter inside the linesman's flag and a receiver, worn by the referee. Similar devices had already been described in previous documents (DE 1 993 964 U), but Kreitlein's radio commander had proved reliable in practice in several test games and was patented.

However, the hopes that, similarly to Ken Aston's penalty cards, his invention would be quickly introduced into football at an international level were soon shattered. The International Football Association Board rejected the innovation based on the grounds that, in case of a change, the existing standards and rules had to be amended on a global level and that the costs of the device would be too high for small countries and teams in lower leagues.

However, 14 years later, FIFA eventually supported the introduction of a radio system for referees and linesmen (a newer model by a Swiss company won the contract). Since the costs for acquiring the radio system are considerable even today, its use is only obligatory in higher leagues and optional in lower leagues. After tests in the UEFA Champions League and some national leagues, referees wore headsets to communicate via radio with their assistant referees in all games of the 2006 FIFA World Cup.

Kreitlein's radio commander never made it to the World Cup stadiums, but credit is due to its inventor for his pioneering work to improve communication on the football pitch.